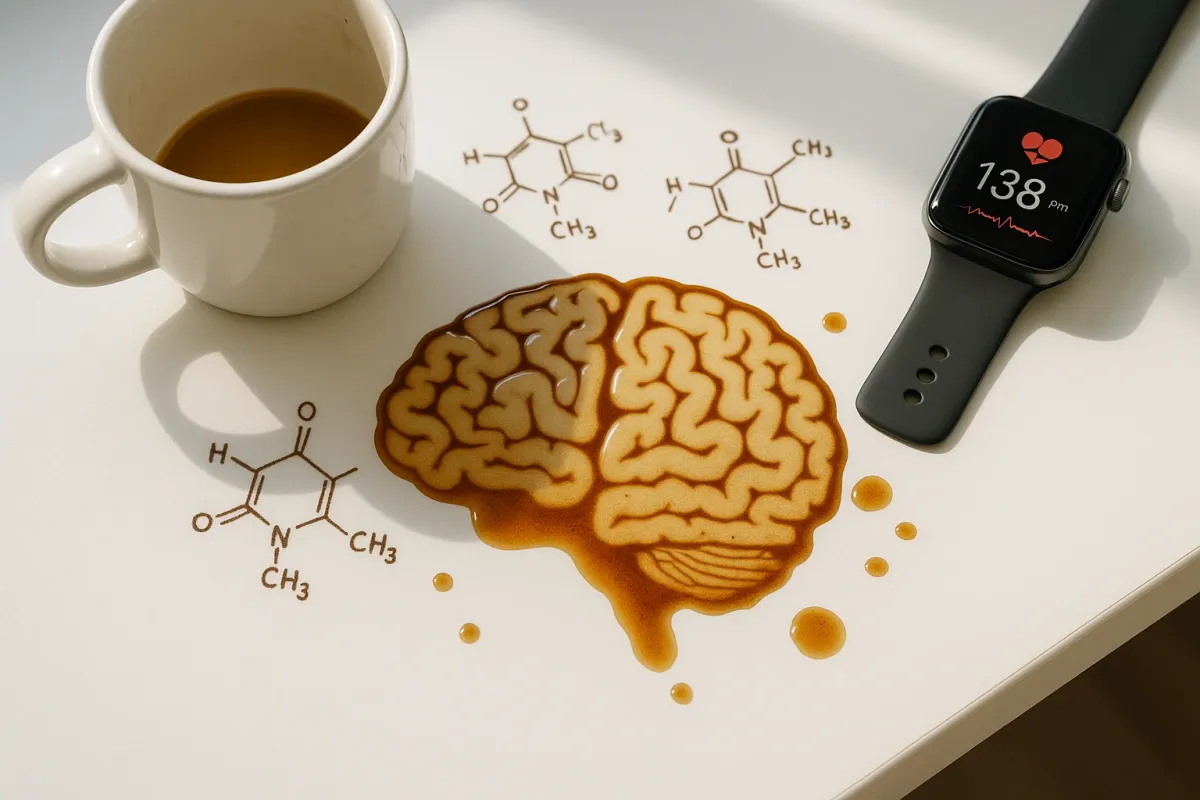

Morning coffee might feel like a small ritual—until it’s splashed all over your counter and snapped for Instagram. A trending “accidental coffee art” photo series is going viral right now, turning messy pours and mug rings into mini masterpieces. It’s lighthearted content, but it also reflects how central coffee (and caffeine) has become to our everyday lives.

As feeds fill with latte swirls and spilled espresso shots, it’s a good moment to ask: what is this daily habit actually doing inside your body? Beyond the aesthetics, there’s a large and growing body of research on caffeine’s effects on performance, mood, sleep, and long‑term health—and how supplements and timing can change that impact.

Below are five evidence‑based insights to help you enjoy your coffee habit more intelligently.

1. Caffeine Works Because It Hijacks Your Sleep Signaling

Caffeine doesn’t “give” you energy; it blocks your ability to feel tired.

Biochemically, caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist. Adenosine is a molecule that builds up in your brain as you’re awake, binding to receptors and making you feel sleepy. Caffeine fits into those same receptors without activating them, so adenosine can’t attach—your brain interprets this as “I’m not tired yet.” Research in humans shows caffeine can improve alertness, vigilance, and reaction time, especially when you’re sleep‑deprived or performing monotonous tasks (Smith, J Psychopharmacol, 2002; McLellan et al., Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2016).

But this comes with a catch: adenosine is still accumulating in the background. Once caffeine wears off, the “sleep pressure” can hit hard, which is why a big afternoon coffee can lead to a late crash. For many people, a moderate dose—roughly 3 mg caffeine per kg of body weight (about 200 mg for a 70‑kg / 155‑lb adult)—is enough for performance benefits without severe jitters. Piling on more doesn’t linearly increase benefits and may worsen anxiety or palpitations, especially in sensitive individuals.

2. Coffee Can Support Long‑Term Health—But It’s Not Magic

Those beautiful coffee shots across social media often come with claims like “coffee is a superfood.” The data are more nuanced—but generally reassuring.

Large observational studies, including cohorts from Harvard and European consortia, consistently find that moderate coffee intake (about 2–4 cups per day) is associated with lower risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, and overall mortality (Ding et al., Circulation, 2015; Poole et al., BMJ, 2017). Both caffeinated and decaf coffee show benefits, suggesting that polyphenols and other bioactive compounds in coffee—like chlorogenic acids—play a role beyond caffeine itself.

However, these are associations, not proof of cause‑and‑effect. Coffee drinkers might differ in other health behaviors, diets, or socioeconomic factors. When you add sugar syrups, whipped cream, and dessert‑level calories to your “coffee,” you’re also adding metabolic load that can offset potential benefits. For most healthy adults, black coffee or lightly sweetened coffee appears compatible with good long‑term health; but coffee isn’t a substitute for movement, sleep, or nutrient‑dense food.

3. Timing Your Caffeine May Matter More Than The Total Dose

Scroll through enough “accidental coffee art” posts and you’ll notice a pattern: most are from early mornings or late‑night study sessions. The clock matters.

Caffeine has a half‑life of about 4–6 hours in most adults, though this can range from 2–10+ hours depending on genetics, liver function, medications, and pregnancy status (Institute of Medicine, 2001). That means a 4 p.m. double espresso can still be in your system when you’re trying to fall asleep at night. Experimental sleep‑lab studies show that caffeine taken even 6 hours before bedtime can reduce total sleep time and increase awakenings (Drake et al., J Clin Sleep Med, 2013).

From a performance and recovery perspective:

- **Morning:** For early risers, waiting 60–90 minutes after waking before your first coffee may work better with your natural cortisol rhythm and reduce afternoon slumps.

- **Pre‑workout:** A dose of 3–6 mg/kg about 45–60 minutes before training can enhance endurance, high‑intensity performance, and perceived effort (Grgic et al., *Br J Sports Med*, 2020).

- **Evening:** Many sleep specialists recommend a “caffeine curfew” of at least 6 hours before bedtime—longer if you know you’re sensitive.

If you still want the ritual (and the coffee‑art worthy pour) later in the day, decaf or a half‑caf blend can give you flavor and polyphenols with far less sleep disruption.

4. Genetics and Gut Health Shape Your Caffeine Response

Not everyone reacts to coffee the same way. Some people can sip espresso at 9 p.m. and sleep soundly; others feel wired from a single morning latte. Science is starting to explain why.

Variants in the CYP1A2 gene affect how quickly your liver enzymes metabolize caffeine. “Fast metabolizers” clear caffeine more rapidly; in certain observational studies, they may even see cardiovascular benefits from moderate intake. “Slow metabolizers” retain caffeine longer and, in some research, may show increased blood pressure or heart‑related risk when consuming higher amounts (Cornelis et al., JAMA, 2006; Palatini et al., Hypertension, 2009). However, results are mixed, and tests are not yet precise enough to dictate strict rules for every individual.

Your gut also plays a role. Coffee influences the microbiome, and early studies show it may increase certain beneficial species like Bifidobacteria in some people (Jaquet et al., Food Res Int, 2009). At the same time, individuals with IBS, reflux, or gastritis can find coffee irritating, especially on an empty stomach. If you feel anxious, shaky, or get GI upset from coffee or caffeine supplements, it’s a signal to adjust:

- Reduce total daily intake.

- Avoid stacking coffee with high‑dose caffeine pills or energy drinks.

- Take caffeine with food rather than fasted, if your stomach is sensitive.

- Consider trialing lower‑caffeine or decaf options.

Listening to how your body responds is as important as what the averages show in studies.

5. Coffee, Caffeine Supplements, and “Energy” Products Are Not Interchangeable

The viral “coffee art” trend focuses on beverages, but many health‑conscious people are getting caffeine from multiple sources—pre‑workouts, “energy” capsules, green tea extracts, and nootropic blends—often without realizing how much they’re stacking.

Here are key differences grounded in current evidence:

- **Brewed coffee** provides caffeine plus a complex mix of polyphenols, diterpenes, and minerals. Filtered methods (like drip or pour‑over) remove much of the cafestol and kahweol that can raise LDL cholesterol, while unfiltered methods (French press, boiled coffee) preserve them (Urgert & Katan, *N Engl J Med*, 1997).

- **Caffeine tablets/powders** deliver a precise dose, which can be helpful in research and performance settings. But concentrated forms have caused serious overdoses and even deaths when misused. The FDA has warned consumers about bulk pure caffeine products because a single teaspoon can equal dozens of cups of coffee.

- **Energy drinks and “focus” shots** often combine caffeine with sugar, amino acids (like taurine), B‑vitamins, and herbal extracts (like guarana or yerba mate). These blends can raise heart rate and blood pressure more than coffee alone in some individuals, and large volumes can add significant calories and sugar.

- **“Natural” stimulant blends** (green tea extract, guarana, kola nut) still deliver caffeine; labeling can be less clear, and total caffeine content is sometimes under‑reported.

For adults, many public‑health authorities suggest staying below about 400 mg caffeine per day from all sources (roughly 3–4 strong coffees), with lower limits for pregnancy, certain medical conditions, and adolescents. If you’re already drinking coffee, think of supplements and energy products as additions, not replacements, and factor everything into your daily total.

Conclusion

The rise of “accidental coffee art” on social media is a fun reminder of how deeply coffee is woven into our lives. But behind every photogenic spill and latte swirl is a powerful psychoactive compound shaping your alertness, sleep, performance, and long‑term health.

Used thoughtfully—at the right dose, time, and in the right form—caffeine can be a legitimate performance and mood tool with a surprisingly solid research base. Overused or layered with high‑dose supplements and sugary energy products, it can quietly undermine your sleep, recovery, and cardiovascular health.

You don’t need to give up your daily ritual to protect your health. Start by knowing roughly how much caffeine you’re actually consuming, experiment with timing, and pay attention to your personal responses. That way, the only chaos coffee brings to your day is the kind that looks good in a photo.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Research.