For years, supplement research was treated as a simple question: “Does this ingredient work, yes or no?” Today, the science is much more nuanced. Researchers are factoring in psychology, genetics, real‑world behavior, and long‑term safety in ways that make older “miracle pill” claims look outdated. If you care about what actually moves the needle for your health, understanding how modern research is evolving can help you separate promising formulations from wishful marketing.

Below are five evidence‑based insights from current research that can change how you read labels, interpret studies, and decide what’s worth taking.

1. The Placebo Effect Isn’t Noise—It’s a Measurable Biology Signal

In supplement trials, people often feel better even when they’re taking an inert capsule. That doesn’t mean the product “works”; it means human expectation is powerful—and measurable.

Clinical research now routinely uses randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled designs because placebo responses can be large, especially for outcomes like pain, mood, fatigue, and sleep quality. Brain imaging studies show that believing you’re getting a helpful treatment can trigger real changes in neurotransmitters, stress hormones, and pain pathways.

For health‑conscious readers, this has two key implications:

- When a study doesn’t use a placebo group, positive results are hard to interpret.

- A supplement that “feels” like it’s working isn’t proof of biological effect; subjective changes need to be backed by objective outcomes (lab values, performance metrics, imaging, or validated symptom scales).

Far from being a nuisance, placebo responses are now studied as a window into how expectation, context, and routine influence health. That’s valuable—just don’t confuse it with evidence that a specific ingredient is uniquely effective.

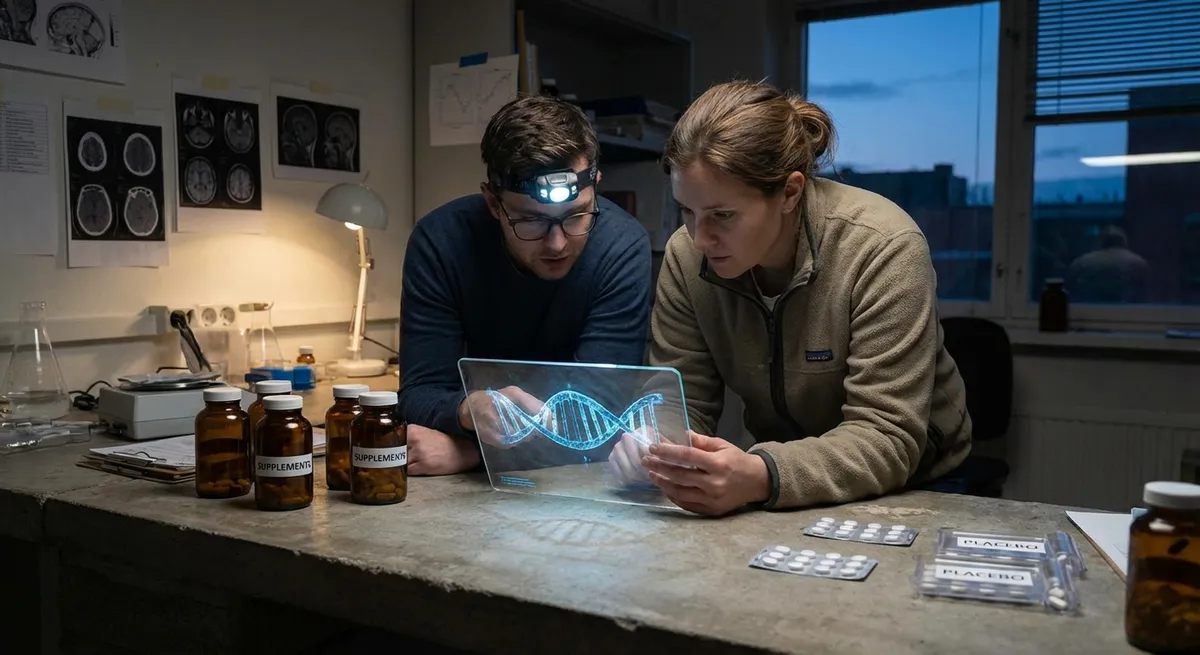

2. Genetics Is Explaining Why Some People Respond and Others Don’t

One reason supplement studies sometimes show “mixed results” is that participants are biologically different. Nutrigenomics—the study of how genes influence nutrient needs and responses—is helping explain those differences.

Examples from published research:

- **Vitamin D**: Variants in genes related to vitamin D binding and metabolism (like *GC* and *CYP2R1*) affect blood vitamin D levels and how strongly people respond to the same dose.

- **Omega‑3 fatty acids**: Genetic differences in fatty acid metabolism can change how much EPA/DHA supplementation shifts triglycerides or inflammation markers.

- **Caffeine**: Common variants in the *CYP1A2* gene influence how fast people clear caffeine, altering its effects on performance, sleep, and blood pressure.

This doesn’t mean you need a genetic test to benefit from basic supplementation. But it does mean:

- “No benefit on average” in a trial may still hide meaningful benefit for specific subgroups.

- Personalized dosing and ingredient selection is an emerging research focus, especially for nutrients affected by common genetic variants.

As more trials stratify participants by genotype, we can expect clearer answers about who is most likely to benefit from which supplements—and at what doses.

3. Real‑World Data Is Challenging Short, Perfect Lab Studies

Traditional supplement studies often put people in highly controlled conditions for a few weeks or months: fixed doses, strict schedules, and regular monitoring. That’s helpful for isolating effects, but it doesn’t look much like real life.

Researchers are now leaning more on:

- **Long‑term cohort studies**, which track diet, supplement use, and health outcomes in large populations over years or decades.

- **Registry and electronic health record data**, which help identify patterns in supplement use and outcomes across millions of people.

- **Pragmatic trials**, which test interventions in typical, everyday settings rather than tightly controlled lab environments.

These approaches have revealed important nuances:

- Supplements that look promising in short trials don’t always translate to better long‑term health outcomes.

- People who take supplements often differ in many ways (diet, exercise, healthcare access), and careful statistical adjustment is needed to avoid over‑crediting pills for benefits that come from overall lifestyle.

- Adherence drops in real life; what works in a monitored study may be less impactful if most people forget half their doses.

For you, this means a single, short‑term study showing a lab improvement (like a small shift in a biomarker) isn’t the full story. Stronger evidence comes when short‑term trials, long‑term observational data, and real‑world outcomes point in the same direction.

4. Safety Research Now Looks Beyond Obvious Side Effects

Supplements are often marketed as “natural” and therefore “safe,” but safety is a research topic in its own right—especially for long‑term, daily use.

Modern safety research goes beyond tracking immediate side effects like nausea or headaches. It increasingly includes:

- **Liver and kidney monitoring**, particularly for herbal products, high‑dose vitamins, and bodybuilding or weight‑loss formulas.

- **Drug–supplement interaction studies**, examining how ingredients like St. John’s wort, high‑dose biotin, or certain minerals interact with prescription medications or lab tests.

- **Upper intake level research**, determining at what daily doses fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), minerals (iron, zinc, selenium), and some antioxidants may cause harm over time.

Key takeaways for health‑conscious users:

- “More” is not automatically better; some nutrients have a U‑shaped curve where both deficiency and excess can be risky.

- High‑dose or multi‑ingredient formulations deserve extra scrutiny, especially if you’re also taking prescription medications.

- Case reports and adverse event monitoring systems (like those used by the FDA) are important early warning tools; serious but rare side effects won’t show up in small studies.

Evidence‑based supplement decisions weigh both potential benefit and potential risk—particularly for ingredients taken daily and indefinitely.

5. Combination Formulas Are Being Tested as Systems, Not Just Ingredients

Many products now combine multiple vitamins, minerals, botanicals, and bioactives. That creates a research challenge: individual ingredients may have some evidence, but how do they behave together?

Researchers are increasingly:

- Designing trials that test **the full formula**, not just one “hero” ingredient.

- Looking at **synergy and antagonism**, where one ingredient may enhance, blunt, or change the absorption or action of another.

- Using **systems biology approaches**, modeling how combinations affect networks like inflammation, oxidative stress, gut microbiome composition, or metabolic pathways.

For example, some studies examine how adding vitamin C or certain polyphenols affects the absorption of plant‑based iron, or how probiotics and prebiotics in the same formula alter gut‑derived metabolites compared to either alone.

For consumers, this means:

- Evidence for an individual ingredient (like curcumin or magnesium) doesn’t automatically apply to every blend that includes it.

- High‑quality research will reference trials on the actual product or a very similar combination, not just loosely related single‑ingredient data.

- When reading about a supplement, it’s useful to ask: Did the study test this exact formula, or just one component?

As combination research grows, expect more nuanced claims: not just “this ingredient works,” but “this specific combination, at these doses, under these conditions, produced these measured effects.”

Conclusion

Modern supplement research is evolving quickly. Placebo effects are understood as real biology, not just background noise. Genetics is explaining why some people respond while others don’t. Real‑world data is challenging neat laboratory stories. Safety studies are treating long‑term, daily use as seriously as benefit claims. And complex formulas are finally being tested as systems, not collections of isolated ingredients.

If you’re health‑conscious, the practical message is clear: look for research that is placebo‑controlled, transparent about who was studied, grounded in both short‑term and long‑term data, serious about safety, and relevant to the actual product you’re considering. That kind of evidence won’t guarantee a miracle—but it will help you choose supplements that are more aligned with how health really works in the body, not just how marketing describes it.

Sources

- [National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) – Placebo Effect](https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/placebo-effect) - Overview of how placebo responses are studied and why they matter in clinical research

- [Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Vitamin D and Health](https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/vitamin-d/) - Discusses genetic influences on vitamin D levels and response to supplementation

- [NIH Office of Dietary Supplements – Dietary Supplements: What You Need to Know](https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/WYNTK-Consumer/) - Evidence‑based guidance on benefits, risks, and safety considerations for supplements

- [U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – Dietary Supplements](https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements) - Details on regulation, safety monitoring, and adverse event reporting for supplements

- [Mayo Clinic – Nutrigenomics: Genes and Nutrition](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/nutrigenomics/art-20167346) - Explains how genetic variation affects responses to nutrients and informs emerging research

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Research.