When you see a bold claim on a supplement bottle, there’s usually (or at least there should be) a trail of research behind it. But what actually happens between a promising ingredient in a petri dish and a capsule on the shelf? Understanding how ingredients are studied doesn’t just satisfy curiosity—it helps you spot what’s likely to work, what’s overhyped, and what still has big question marks.

This article walks through how supplement ingredients are researched, with five key evidence-based principles that can help you read claims with more confidence—and a bit more healthy caution.

1. Lab vs. Human Studies: Why the Model Matters

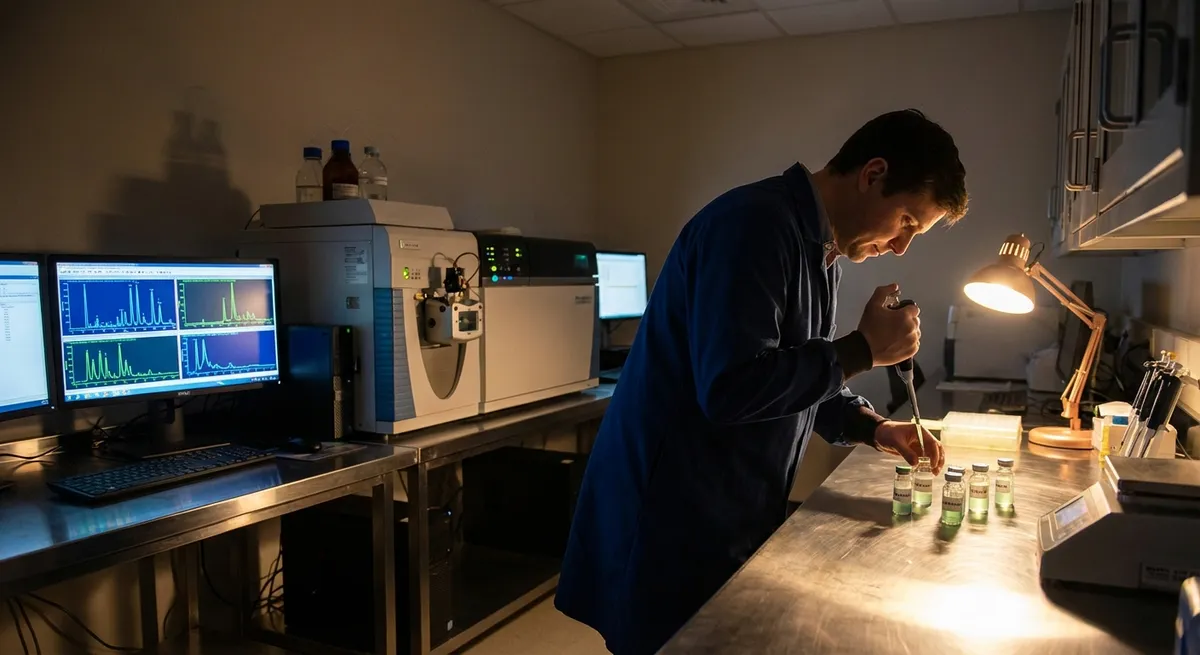

Most supplement ingredients start their journey in preclinical research: cell cultures (in vitro) and animal models (in vivo). These early studies are essential, but they don’t tell the whole story for humans.

Researchers often begin with in vitro experiments to see if an ingredient affects specific pathways—like inflammation markers, oxidative stress, or receptor activity. If the signal looks promising, the next step may be animal studies, where scientists can explore dose ranges, safety signals, and mechanisms in a living system.

The key limitation: humans are more complex. Metabolism, gut absorption, other medications, and lifestyle factors all influence how a compound behaves. Many compounds that look potent in a dish are poorly absorbed, rapidly broken down, or behave differently in people. That’s why claims based solely on cell or animal data are considered preliminary.

For consumers, the practical takeaway is straightforward: lab and animal data can suggest potential, but they can’t prove that an ingredient is effective for you. When you evaluate a supplement, look for human data—and be wary when the strongest support never gets beyond preclinical research.

2. Dose and Formulation: The “Details” That Change Everything

Even when an ingredient has human research, dose and formulation can completely change outcomes.

Clinical studies typically use a specific amount of a defined form: for example, 1,000 mg of EPA+DHA from concentrated fish oil, or 1.6–3.2 g of creatine monohydrate per day. That exact dosage and chemical form matter, because they determine how much of the active compound gets into your bloodstream and reaches tissues.

Two products can list the same ingredient on the label but differ in:

- **Chemical form** (e.g., magnesium oxide vs. magnesium citrate)

- **Delivery format** (tablet, capsule, liquid, liposomal)

- **Standardization** (how much of the active compound is present)

- **Additives and co-ingredients** (which can help or hinder absorption)

In research, these parameters are carefully controlled. In the market, they’re often changed for cost, stability, or marketing reasons. A supplement may cite a study using one form and dose, but the product itself may contain a lower dose, a different form, or a non-standardized extract.

This is why evidence-based evaluation needs to connect three dots: (1) the ingredient studied, (2) the form and dose used, and (3) what’s actually in the bottle. When those don’t match, you can’t assume the same results apply.

3. Study Design: How Trials Are Built to Reduce Bias

When we talk about “gold standard” evidence in supplement research, we’re usually referring to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The way these trials are designed can either strengthen or weaken how much we trust the results.

Key design elements that matter:

- **Randomization**: Participants are assigned to groups by chance, which helps balance out confounding factors between the supplement and control groups.

- **Control group**: Often a placebo, but sometimes a comparison to a standard treatment. This tells us what would likely happen *without* the supplement.

- **Blinding**: Ideally, neither participants nor researchers know who’s getting the active supplement. This reduces the placebo effect and observer bias.

- **Sample size and duration**: Larger, longer trials are more likely to produce reliable, generalizable results, especially for chronic outcomes like blood pressure or glucose control.

- **Pre-registered outcomes**: When researchers specify main outcomes in advance (e.g., blood pressure reduction, change in LDL cholesterol), it reduces the temptation to “cherry-pick” whatever changed and call it a success.

In the real world, not every supplement trial hits these marks. Some are small, short, or open-label (everyone knows what they’re taking), which makes results more uncertain.

For a health-conscious reader, the question isn’t “Is this study perfect?” but “Given how this trial was designed, how much weight should I give these findings?” Stronger designs support stronger confidence—but no single trial answers everything.

4. From Single Trials to Patterns: Why Replication Matters

One positive trial can be exciting, especially if an ingredient shows benefits in outcomes people care about—energy, sleep, mood, blood markers, or exercise performance. But science leans heavily on replication: seeing similar results in different groups, settings, and research teams.

Supplements often make big claims based on:

- A single small RCT

- An open-label study without a placebo

- Or observational data with many confounding factors

More robust confidence comes when:

- Multiple RCTs show similar effects

- Trials include diverse populations (age, sex, health status)

- Meta-analyses or systematic reviews pool results and evaluate overall strength of evidence

It’s also useful to notice inconsistency: if some trials show a benefit and others don’t, researchers look at who was studied, what dose was used, and how outcomes were measured. For example, an ingredient might help individuals with a deficiency but not those who already have optimal levels, or it might support specific conditions but not general “wellness.”

For you, the practical lens is: “Is this claim supported by a single study, or by a pattern across multiple high-quality trials?” The more consistent and replicated the data, the more confident you can be in a real effect.

5. Safety Signals: How Risks Are Tracked Alongside Benefits

Supplement marketing tends to spotlight benefits, but research also tracks safety—and that evidence deserves just as much attention.

In clinical trials, safety is monitored by:

- **Adverse event reporting**: Participants report side effects, which are categorized by severity and whether they’re likely related to the supplement.

- **Laboratory monitoring**: For some trials, researchers track liver enzymes, kidney function, blood counts, or other markers to catch issues early.

- **Dropout rates**: If many participants stop the supplement due to side effects, that’s an important signal even if serious adverse events are rare.

Beyond trials, post-marketing surveillance systems (such as the FDA’s adverse event reporting system in the United States) collect real-world reports that can reveal rare or delayed risks that small trials can’t detect.

A critical nuance: “Natural” does not mean “risk-free.” Botanical extracts, high-dose isolated nutrients, and combinations of ingredients can interact with medications or underlying conditions. Research helps define not only potential benefits, but also dose thresholds, contraindications, and populations who should use extra caution (such as pregnant individuals, people with chronic disease, or those on prescription drugs).

When you evaluate a supplement, it’s reasonable to ask: what do human data say about safety, at what doses, and over what time frame? Responsible use balances both sides of the evidence, not benefits alone.

Conclusion

Understanding how supplement ingredients are researched turns vague marketing claims into something you can actually evaluate. Cell and animal studies hint at possibilities, human trials test those possibilities in real people, and patterns across many studies tell us how confident to be. Dose and form matter, study design matters, replication matters, and safety data matter just as much as efficacy.

You don’t need to be a scientist to benefit from this process—you just need to know which questions to ask about the research behind an ingredient. With that framework, every new supplement claim becomes less of a gamble and more of an informed decision.

Sources

- [National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements](https://ods.od.nih.gov) – Background on supplement ingredients, fact sheets, and summaries of human research

- [U.S. Food and Drug Administration – Dietary Supplements](https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements) – Regulatory framework, safety information, and adverse event reporting for supplements

- [Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Vitamins and Minerals](https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/vitamins/) – Evidence-based overviews of micronutrients, dosing, and health effects

- [Mayo Clinic – Herbal Supplements: What to Know Before You Buy](https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/consumer-health/in-depth/herbal-supplements/art-20046714) – Discussion of evidence, safety considerations, and how to interpret claims

- [Cochrane Library – Dietary Supplements Topic](https://www.cochranelibrary.com/topic/nutrition/dietary-supplements) – Systematic reviews that evaluate the totality of evidence for various supplement ingredients

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Research.