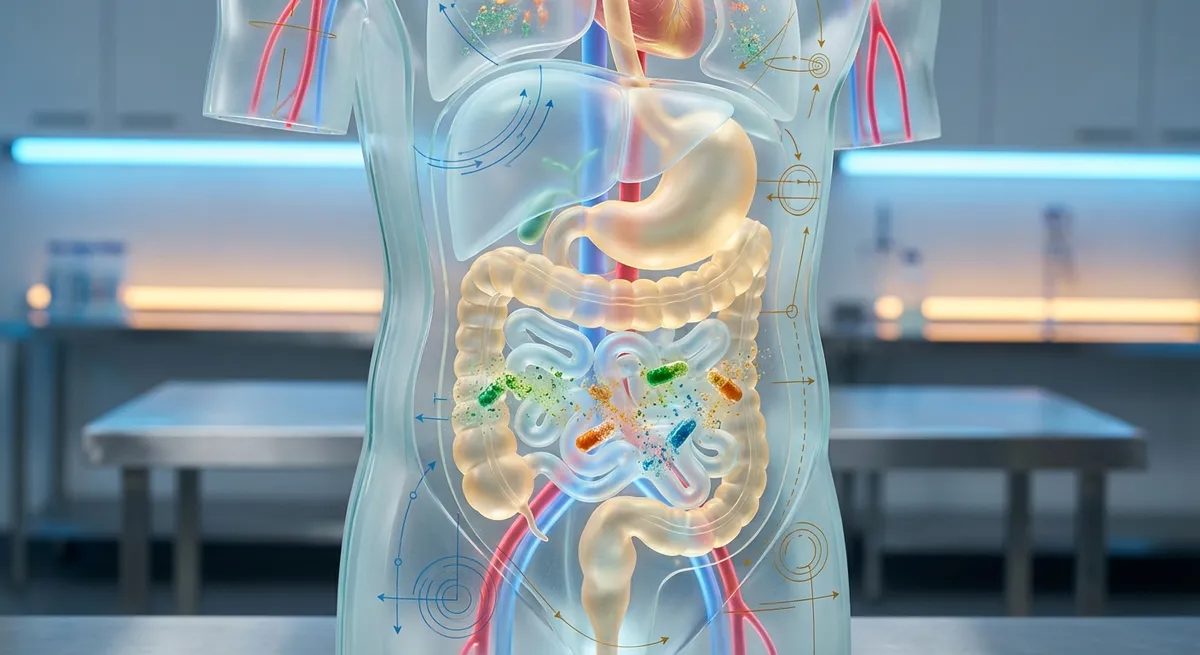

Most supplement advice stops at “take this for energy” or “this helps immunity.” That’s not enough for a health‑conscious reader who wants to understand what’s actually happening between swallowing a capsule and feeling a difference. To use supplements wisely, it helps to see them not as magic bullets, but as active compounds that must survive your digestive system, compete for transport, interact with medications, and be processed by your liver and cells.

This overview looks at how supplements behave inside your body, using five evidence‑based principles that can help you make more informed choices.

---

1. Absorption Starts With the Form You Swallow

The form of a nutrient (its “chemical form”) strongly influences how well your body absorbs it. Two products can list the same milligrams on the label yet behave very differently once they hit your gut.

Chelated minerals (like magnesium glycinate) are bound to amino acids, which may improve tolerance and absorption for some people compared with less soluble forms such as magnesium oxide, which is more likely to cause loose stools. Similarly, iron bisglycinate often causes fewer gastrointestinal side effects than ferrous sulfate, while still effectively raising iron stores.

Fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) need dietary fat and bile acids for proper absorption. Taking vitamin D with a meal that includes healthy fats (like olive oil, avocado, or nuts) can significantly improve uptake compared with taking it on an empty stomach. Water‑soluble vitamins (like vitamin C and most B vitamins) are generally more easily absorbed, but they also have a lower storage capacity in the body, so very high single doses often get excreted in urine rather than used.

Bioavailability (how much of a nutrient actually reaches circulation) is also shaped by your own physiology: stomach acidity, gut health, age, and medications like acid‑suppressing drugs. This is why “more milligrams” on the label doesn’t always translate to “more benefit” in your bloodstream.

---

2. Nutrients Compete and Cooperate Inside Your Gut

Your digestive tract is a crowded, competitive environment. Nutrients often share transporters and pathways, so what you take together matters.

Certain minerals compete for absorption. High doses of supplemental zinc, for example, can inhibit copper absorption over time, potentially leading to deficiency if copper intake is low. Large doses of supplemental calcium can impair iron absorption when taken at the same time, which is particularly relevant for people with anemia or those relying heavily on iron supplements.

Other nutrients work better together. Vitamin D enhances calcium absorption, which is why they are often paired in bone‑support formulas. Vitamin C increases non‑heme iron absorption (the form found in plants and most supplements) in the small intestine, so taking vitamin C alongside iron can make a meaningful difference in how much iron your body retains.

Fiber and phytates (found in whole grains and legumes) can bind minerals like zinc, iron, and magnesium, decreasing their availability. This doesn’t mean these foods are “bad”—they’re generally very healthy—but timing high‑dose mineral supplements away from very high‑fiber meals can sometimes support better absorption, especially when trying to correct a frank deficiency.

Understanding these competition and cooperation patterns helps explain why some people don’t see changes in blood tests or symptoms even when they’re technically “taking the right supplement.”

---

3. Your Liver Turns “Natural” Compounds Into Something New

Once absorbed, many supplement compounds make a critical stop in the liver before circulating widely. This “first‑pass metabolism” can either activate, deactivate, or transform what you’ve taken.

Herbal compounds like curcumin (from turmeric) are metabolized quickly in the liver and gut, which is a major reason isolated curcumin has relatively low systemic bioavailability, even though turmeric as a spice has a long history of traditional use. Formulations that combine curcumin with piperine (from black pepper) or use specialized delivery systems attempt to modify this metabolism, sometimes with measurable effects—but at the cost of also affecting how other compounds are processed.

Your liver also handles fat‑soluble vitamins and many plant polyphenols (like those in green tea extracts or resveratrol). If you already have liver disease or are taking hepatotoxic medications, adding concentrated herbal extracts can increase stress on detoxification pathways. Lab‑measured liver enzymes may rise with certain high‑dose supplements, especially when multiple concentrated botanicals are used together.

“Natural” does not mean “bypasses liver metabolism.” In many cases, the liver is where benefits or harms are largely determined. This is why clinicians pay careful attention to supplement use in people with existing liver conditions or those taking multiple medications processed by similar enzymatic pathways (such as cytochrome P450 enzymes).

---

4. Supplements Can Interact With Medications at the Molecular Level

Drug‑supplement interactions are not just theoretical; they’re a routine concern in clinics and pharmacies. Some supplements alter how medications are absorbed, metabolized, or excreted, changing drug levels in your body.

A classic example is St. John’s wort, which can increase the activity of certain liver enzymes and transport proteins. This speeds up the clearance of many medications (like some antidepressants, birth control pills, and blood thinners), potentially reducing their effectiveness. Grapefruit juice does the opposite with certain drugs—slowing breakdown and raising drug concentrations—illustrating how strongly plant compounds can affect pharmacology.

Mineral supplements can also interact. Calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc can bind to some antibiotics (like tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones) and thyroid medications (levothyroxine), reducing their absorption if taken at the same time. For this reason, clinicians often recommend spacing such drugs and mineral supplements by several hours.

Vitamin K can interfere with the action of warfarin, a common anticoagulant. While consistent vitamin K intake from food is usually encouraged (to avoid big swings in clotting status), sudden changes from high‑dose supplements can disrupt carefully managed dosing.

Because many supplement‑drug interactions are dose‑dependent and pathway‑specific, it’s important to view your supplement regimen as part of your overall medication profile. Bringing actual bottles or a written list to medical visits gives your healthcare team enough detail to identify potential conflicts.

---

5. Deficiency, Sufficiency, and “More Is Better” Myths

The effects of a supplement depend heavily on your starting point. Correcting a genuine deficiency can dramatically improve health; adding more of a nutrient when you are already sufficient usually offers diminishing returns and sometimes added risk.

For example, vitamin D supplementation clearly improves bone health and reduces fracture risk in people who are deficient or institutionalized with low sun exposure. In contrast, large trials of high‑dose vitamin D in generally healthy, community‑dwelling adults with adequate baseline levels show more modest or uncertain benefits for many outcomes, like cardiovascular disease or cancer.

Similarly, omega‑3 fatty acid supplements can lower triglycerides and may benefit heart health in select high‑risk individuals, but routine high‑dose use in low‑risk populations does not replicate the same degree of benefit seen in specific patient groups, and can slightly increase bleeding risk in some contexts.

Fat‑soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) can accumulate in the body. Very high intakes, especially from multiple products (a multivitamin plus separate “mega‑dose” capsules, for instance), can lead to toxicity over time. Excess vitamin A can cause liver damage and bone problems; too much vitamin E may increase bleeding risk in some individuals.

Understanding the difference between:

- fixing a deficiency,

- maintaining sufficiency, and

- pushing into unnecessary excess

helps orient supplement use toward measured, evidence‑based targets rather than open‑ended “more is better” thinking. Blood tests and professional guidance can be especially useful for nutrients with narrower safety windows or when multiple products contain overlapping ingredients.

---

Conclusion

Every capsule, powder, or gummy you take has to navigate digestion, competition with other nutrients, liver metabolism, and potential interactions with medications before it can do anything useful for your cells. The real story of supplements is less about quick fixes and more about context: your diet, your health status, your medications, and your specific biological needs.

Approaching supplements as active compounds—not wellness accessories—opens the door to smarter decisions: choosing effective forms, timing doses thoughtfully, checking for interactions, and targeting actual deficiencies rather than chasing generalized promises. When those pieces align, supplements can move from guesswork toward a more rational, evidence‑informed part of your health strategy.

---

Sources

- [National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements](https://ods.od.nih.gov/) – Fact sheets on vitamins, minerals, and herbs, including safety, interactions, and recommended intakes

- [U.S. Food & Drug Administration – Dietary Supplements](https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements) – Regulatory information, safety alerts, and consumer guidance on supplement use

- [Mayo Clinic – Herbal supplements and heart medicines: A risky mix?](https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/herbal-supplements/art-20046488) – Overview of common herb–drug interactions and cardiovascular considerations

- [Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Vitamins and Minerals](https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/vitamins/) – Evidence‑based discussion of nutrient roles, deficiency, and supplementation

- [National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH)](https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/dietary-and-herbal-supplements) – Research summaries on dietary and herbal supplements, including safety and efficacy

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Supplements.