Supplements don’t act in a vacuum. The same capsule can have very different effects depending on who takes it, what else they eat, when they take it, and even their gut microbiome. Understanding these “hidden variables” is one of the most underrated ways to make supplements safer, smarter, and more effective.

This article walks through five evidence-based factors that quietly influence how your body responds to supplements—so you can move away from guesswork and closer to intentional use.

Your Baseline Status: The Starting Point Changes the Outcome

What you already have in your system often matters more than what’s on the label.

For many nutrients, the benefit curve isn’t “more is better” but “too little is a problem, enough is a win, too much can be harmful.” Vitamin D is a good example: people with clear deficiency tend to see meaningful benefits from supplementation (like improved bone health and possibly immune support), while those with adequate levels often see smaller or no added gains, and very high intakes over time can raise the risk of toxicity. Similar patterns show up with iron, vitamin B12, and iodine.

This is why the same dose that helps one person can be unnecessary—or even risky—for another. Blood work, diet history, and health status shape whether a supplement is filling a real gap or just stacking more on top of sufficiency. In research, trials that target people who are deficient frequently show stronger effects than those done in generally well‑nourished populations.

For health‑conscious users, the practical takeaway is to think “test and assess” instead of “just in case.” If possible, objective measures (like serum vitamin D, ferritin for iron, or B12 levels) plus a review of your diet and symptoms provide a clearer picture than relying on general marketing claims. The more you know about your baseline, the easier it is to choose supplements that are likely to matter—and skip the ones that won’t.

Timing and Food: When and How You Take a Dose Alters Absorption

The timing of a supplement and whether you pair it with food can significantly alter how much your body actually absorbs.

Fat‑soluble nutrients—such as vitamins A, D, E, and K, as well as compounds like curcumin—tend to be better absorbed when taken with a meal that contains some dietary fat. In contrast, some minerals like iron are more readily absorbed on an empty stomach but can be rougher on digestion; taking them with a small snack may reduce side effects at the cost of slightly lower absorption, which can still be clinically acceptable.

Caffeine‑containing supplements (like some pre‑workouts or fat burners) interact with your circadian rhythm and sleep. Taken late in the day, the same dose that feels “energizing” at 10 a.m. can disrupt sleep quality at 9 p.m., indirectly affecting recovery, appetite regulation, and next‑day performance. Melatonin works the opposite way: used at the wrong time relative to your usual sleep schedule, it can shift your internal clock in directions you may not intend.

Even multi‑ingredient products can have time‑sensitive components. Some compounds that support training performance (such as beta‑alanine or caffeine) have clear pre‑exercise timing windows, while others (like creatine) rely more on consistent daily intake than specific timing around workouts.

The key principle: check whether your supplement is fat‑soluble or water‑soluble, stimulant‑containing or sleep‑supporting, and match its timing and context (with or without food) to how the ingredient is actually absorbed and used, not just what fits your routine by default.

Interactions With Medications and Other Nutrients: Synergy and Conflict

Supplements can cooperate with each other—or get in each other’s way. They can also meaningfully interact with prescription medications.

Minerals are a common site of competition. High doses of zinc taken over time can reduce copper absorption; excessive calcium intake, especially from supplements, can interfere with iron and possibly zinc absorption when taken together. That means a heavily loaded “all‑in‑one” formula may not always be your friend if it piles competing minerals into one big serving.

On the medication side, some well‑known interactions are clinically important. St. John’s wort can speed up the breakdown of certain drugs (including some antidepressants, birth control pills, and transplant medications) by inducing liver enzymes, potentially reducing their effectiveness. High‑dose vitamin K can oppose the action of warfarin, a blood thinner that relies on stable vitamin K levels to work safely. Even something as common as magnesium can influence the absorption of certain antibiotics when taken at the same time.

There are also examples of helpful synergy: vitamin D often pairs with calcium and vitamin K2 for bone health, omega‑3 fatty acids may complement statins in specific cardiovascular contexts, and vitamin C can enhance iron absorption from plant sources. But synergy only helps when doses are appropriate and your individual situation supports the combination.

Because interactions are both common and highly individual, it’s wise to treat new supplements like new medications: bring a full list (including doses and brands) to a qualified healthcare professional, especially if you’re on prescription drugs, have chronic conditions, or are considering herbal products.

Your Gut Microbiome: The “Middleman” Between Capsule and Cells

Many supplements don’t act directly on your body; they act on your microbiome first, or are transformed by it before they reach your tissues.

Prebiotics (such as inulin, fructooligosaccharides, and resistant starch) are designed to feed beneficial bacteria, which in turn produce short‑chain fatty acids like butyrate that support gut barrier integrity, immune modulation, and energy metabolism. The exact response, though, depends heavily on which microbes you already host. Two people can take the same prebiotic and see very different changes in gas, bloating, or metabolic markers.

Herbal compounds and polyphenols (for example, green tea catechins or curcumin) also depend on microbial enzymes to activate some of their metabolites. If your microbiome composition differs from the populations studied in trials, your real‑world response may be stronger, weaker, or simply different than the average effect reported.

Probiotics add another layer. Most commercial probiotics contain a limited set of strains at defined doses, yet studies show that strain identity, viability, and the surrounding “ecosystem” in your gut all shape whether those strains colonize temporarily, interact with your immune system, or simply pass through. In some cases—such as immediately after certain antibiotic courses—your own microbiome can recover just as effectively as or even better than generic probiotic blends, depending on the context.

For users, this means gut‑focused supplements should be approached experimentally and patiently: start low, change one variable at a time, and track specific outcomes (stool patterns, digestion comfort, skin changes, energy, or lab markers where appropriate). Your microbiome is unique, and your supplement strategy should acknowledge that.

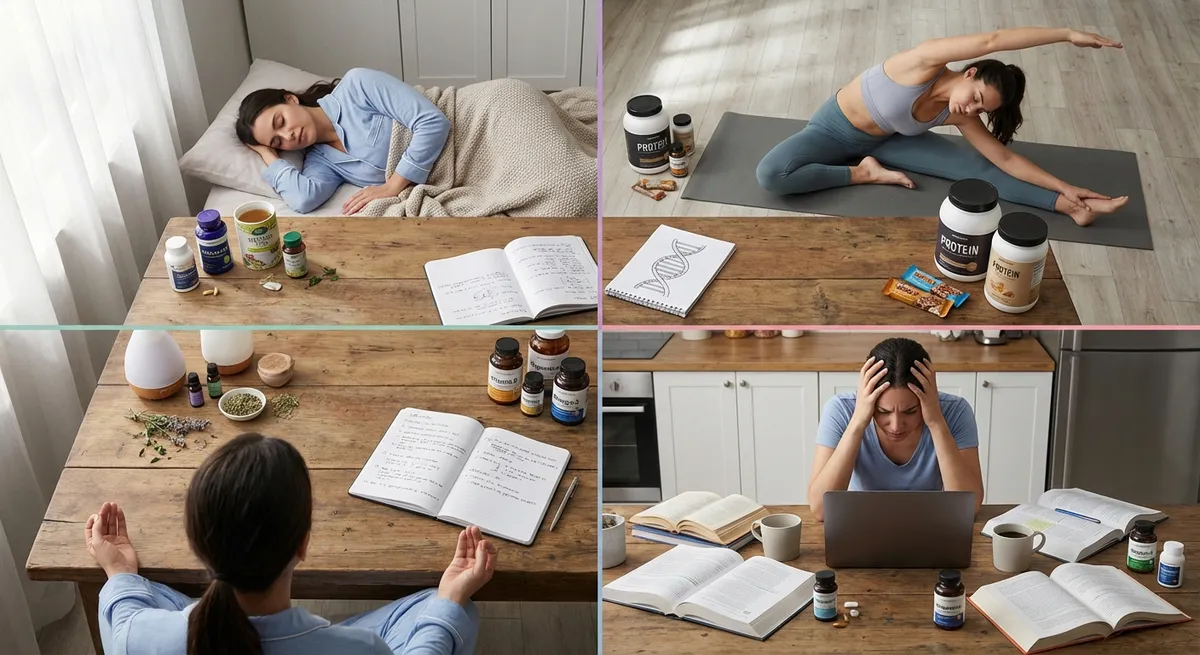

Lifestyle Foundations: Why Habits Still Decide Most of the Outcome

Lifestyle can quietly determine whether a supplement delivers its potential or barely moves the needle.

Sleep, for instance, is deeply tied to metabolic health, immune function, and hormone balance. Taking melatonin or magnesium for sleep while routinely getting only 4–5 hours of rest due to schedules, screens, or work demands is unlikely to replicate the benefits seen in studies that assume adequate sleep opportunity. Similarly, omega‑3 supplementation may support cardiovascular and inflammatory markers, but its impact will be limited if it’s layered on top of chronic smoking, ultra‑processed diets, or persistent high blood pressure that isn’t otherwise managed.

Exercise changes how your body uses nutrients and ergogenic aids. Creatine, protein supplements, and certain performance boosters are most effective in the context of consistent training that provides the stimulus your muscles and nervous system need. Without that stimulus, the gains often seen in research simply have nowhere to land.

Nutrition itself is a major co‑determinant. A generally balanced diet rich in whole foods provides not just isolated vitamins, but fiber, phytonutrients, and cofactors that help your body use both food and supplements efficiently. In contrast, relying heavily on supplements to “cover” for an otherwise nutrient‑poor diet tends to produce disappointing real‑world results.

The big picture: supplements can refine, support, or correct specific issues, but they rarely replace foundational habits. When your sleep, movement, and basic nutrition are at least reasonably in place, the same supplement program will almost always work better—and you may find you need fewer products than you thought.

Conclusion

How well a supplement works for you depends on far more than its ingredient list. Your baseline nutrient status, timing and food context, interactions with other compounds, the state of your gut microbiome, and your everyday lifestyle all shape the true effect of what you swallow.

When you treat supplements as one piece of a broader system—rather than quick fixes—you’re more likely to see meaningful benefits and less likely to waste time, money, or health on products that don’t fit your situation. Asking “what variables am I missing?” is one of the most powerful questions a health‑conscious user can carry into their supplement decisions.

Sources

- [National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements – Vitamin D Fact Sheet](https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-Consumer/) – Overview of vitamin D functions, deficiency, safety, and dosage ranges

- [Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – The Nutrition Source: Vitamin and Mineral Supplements](https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/vitamins/) – Evidence‑based discussion of who benefits from supplements, nutrient interactions, and risks

- [U.S. Food and Drug Administration – Tips for Dietary Supplement Users](https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/tips-dietary-supplement-users) – Guidance on safety, medication interactions, and working with healthcare professionals

- [Mayo Clinic – Probiotics: What You Need to Know](https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-probiotic/art-20322650) – Explanation of how probiotics interact with the gut and factors that influence their effects

- [Cleveland Clinic – Medication and Supplement Interactions](https://health.clevelandclinic.org/supplements-and-prescription-drugs-a-dangerous-mix) – Practical review of common and clinically important drug–supplement interactions

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Supplements.