Nutrition isn’t just about calories, macros, or “eating clean.” Every meal is a set of chemical signals your body has to interpret. The right signals can support energy, focus, and long-term health; the wrong ones can quietly push your metabolism, hormones, and inflammation in the opposite direction.

For health-conscious readers, understanding how food behaves like information—rather than just fuel—can make nutrition choices clearer, more strategic, and less confusing. Below are five evidence-based insights that show what’s really happening between your plate and your cells.

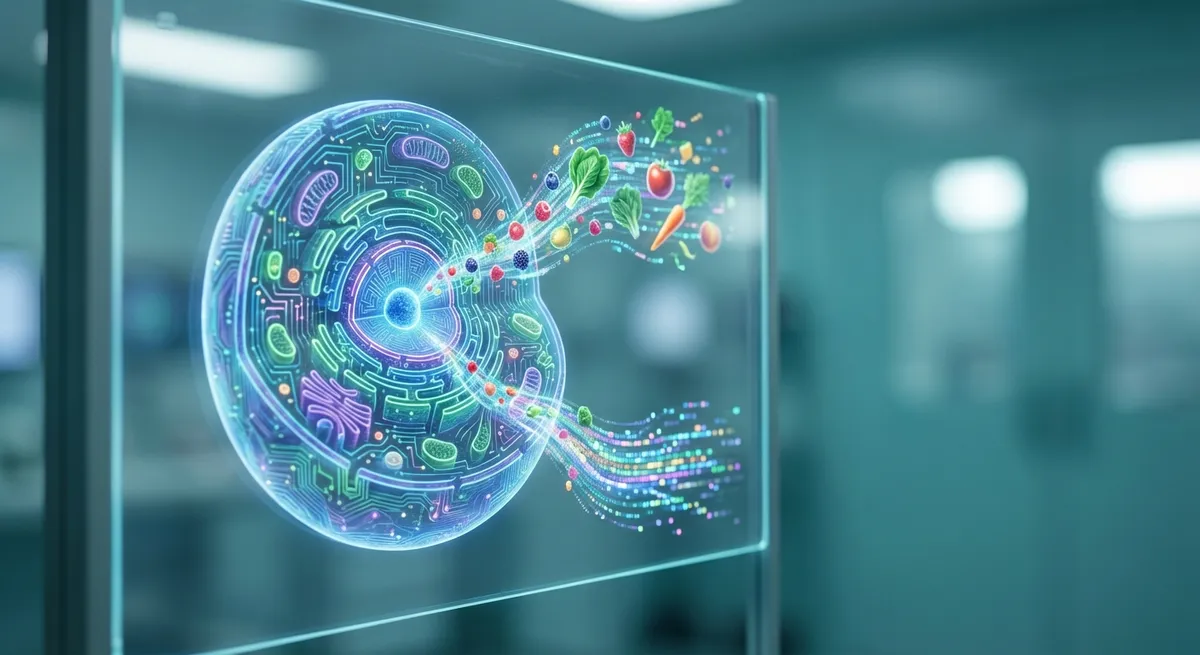

Food as Cellular Signals, Not Just Fuel

Your body doesn’t “see” food as recipes or labels—it sees molecules. Those molecules act like inputs your cells use to decide what to do next: turn genes on or off, store or burn energy, ramp up or calm down inflammation.

Polyphenols in berries, for example, don’t just add color and flavor. They interact with signaling pathways involved in oxidative stress and inflammation, potentially protecting blood vessels and brain cells over time. Omega-3 fats from fish influence how cell membranes are built, which affects how cells respond to hormones and immune signals.

Protein intake also acts like a message, especially for muscle tissue. When you eat enough high‑quality protein, it triggers muscle protein synthesis, a repair and rebuilding process that helps preserve muscle as you age. On the flip side, frequent large doses of added sugars can signal your body to continually spike insulin, which over time is linked to insulin resistance and higher risk of type 2 diabetes.

Thinking of food as information helps explain why two diets with the same calories can produce very different outcomes. It’s not only “how much” you eat; it’s “what messages” your food is sending.

Fiber: The Underrated Infrastructure of Metabolic Health

Fiber rarely gets the spotlight that protein or “superfoods” get, but it quietly supports multiple systems at once. It slows digestion, helps stabilize blood sugar, supports healthy cholesterol levels, and feeds beneficial gut bacteria that produce compounds like short-chain fatty acids—important for colon health and possibly immune regulation.

Soluble fiber (found in foods like oats, beans, apples, and flaxseed) forms a gel-like substance in the gut, which can help blunt blood sugar spikes after meals and modestly lower LDL (“bad”) cholesterol. Insoluble fiber (in foods like whole grains, vegetables, and nuts) adds bulk to stool and supports regular bowel movements.

Population studies consistently link higher dietary fiber intake with lower risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. Yet many people fall well below recommended daily intake. Adults are typically advised to aim around 25–38 grams per day, depending on age and sex, but average intake is often barely half that.

A practical approach is to anchor each meal around at least one high-fiber food—such as beans, lentils, intact whole grains, vegetables, or berries—rather than thinking of fiber as an afterthought or only a “digestive” concern.

Protein Quality, Timing, and the Aging Body

As people age, the body becomes less efficient at turning dietary protein into muscle, a process called “anabolic resistance.” That doesn’t mean muscle loss is inevitable—it means protein choices and distribution across the day start to matter more.

High‑quality protein sources (those that provide all essential amino acids in good proportions) include animal proteins like eggs, dairy, fish, and meat, as well as soy and certain combinations of plant proteins. One key amino acid, leucine, plays a particularly strong role in triggering muscle protein synthesis.

Research suggests that for older adults, evenly spreading protein across meals may be more effective than front‑loading it into a single large dinner. Instead of one very high‑protein meal and two low‑protein meals, three moderate‑protein meals can send repeated “rebuild” signals to muscle tissue.

For most generally healthy adults, a total daily protein intake modestly above the minimum recommendation can help support muscle maintenance, especially if combined with resistance training. The exact amount should be tailored to individual health status, activity level, and medical guidance, but the concept is the same: muscle is metabolically active tissue, and diet plus movement work together to preserve it over time.

Ultra-Processed Foods and the Appetite Feedback Loop

Not all processing is harmful—frozen vegetables and plain yogurt are processed but can be highly nutritious. The concern centers more on ultra-processed foods: products that are heavily refined, often high in added sugar, refined starches, unhealthy fats, and salt, and typically low in fiber and intact nutrients.

These foods are designed to be hyper‑palatable—easy to overeat and quick to digest. Their structure and composition can bypass some of the body’s natural satiety signals. In controlled studies where people were allowed to eat as much as they wanted, diets built around ultra-processed foods led participants to consume substantially more calories and gain weight compared with minimally processed diets, even when the meals were matched for macronutrients.

Mechanisms may include faster eating, weaker stretch and nutrient signals in the gut, and frequent spikes and crashes in blood sugar that can drive further hunger. Over time, a pattern of high intake of ultra-processed foods is associated with increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and overall mortality.

A realistic goal isn’t necessarily zero ultra-processed foods, but shifting the default. Center most meals on whole or minimally processed foods—vegetables, fruits, beans, whole grains, nuts, seeds, eggs, fish, and unflavored dairy—and treat highly refined snacks and ready-to-eat products as occasional, not routine, staples.

Micronutrients and “Hidden” Deficiencies You Might Not Feel (Yet)

Energy, mood, and immune resilience are influenced not just by macros but also by vitamins and minerals that quietly support metabolism, nerve function, and cellular repair. Mild deficiencies often develop slowly and may not be obvious at first.

Iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium, and iodine are common nutrients of concern worldwide, though the specific risks vary by region, diet pattern, and life stage. For example, low vitamin D status is prevalent in many populations, especially in areas with limited sun exposure or among people who spend most of their time indoors. Iron deficiency is common among menstruating individuals, pregnant women, and some athletes.

These micronutrients are involved in key bodily functions: vitamin D in bone health and immune function; iron in oxygen transport; B12 in nerve health and red blood cell production; iodine in thyroid hormone synthesis. Marginal deficiencies can manifest as fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance, mood changes, or increased susceptibility to infections—but these signs are nonspecific and easy to attribute to “stress” or “getting older.”

Addressing micronutrient status should ideally start with diet: a variety of nutrient‑dense foods across food groups. In some cases, targeted supplementation under professional guidance may be appropriate, particularly when dietary limitations, medical conditions, or life stages (like pregnancy) increase nutrient needs. Testing and personalized advice from a qualified healthcare provider can help avoid both deficiencies and unnecessary or excessive supplementation.

Conclusion

Nutrition choices quietly shape how your cells behave—how they handle energy, respond to stress, and repair themselves over time. When you see food as information rather than just fuel, patterns emerge:

- Fiber helps stabilize your metabolism and nourish your gut.

- Protein quality and distribution support muscle, especially as you age.

- Ultra-processed foods can interfere with appetite regulation and long-term health.

- Micronutrients, though easy to overlook, are essential for day‑to‑day function and resilience.

You don’t have to overhaul everything at once. Even small, consistent shifts—like adding a high‑fiber food to each meal, choosing a minimally processed option when possible, or reassessing your protein and micronutrient intake—can change the “messages” your nutrition sends to your body in a positive direction.

Sources

- [Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health – Fiber](https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/carbohydrates/fiber/) - Overview of fiber types, health benefits, and intake recommendations

- [National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements – Protein Fact Sheet](https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Protein-Consumer/) - Evidence-based information on protein needs, sources, and health considerations

- [National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements – Vitamin D Fact Sheet](https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-Consumer/) - Details on vitamin D roles, deficiency, and sources

- [BMJ – Ultra-processed food and adverse health outcomes](https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l1949) - Research review linking ultra-processed food consumption with health risks

- [World Health Organization – Micronutrient Deficiencies](https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients) - Global perspective on common vitamin and mineral deficiencies and their impact

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to remember from this article is that this information can change how you think about Nutrition.